A little while ago, I wrote this piece about Glasgow poet Liam McCormick’s one-man show, which is based on his book, ‘BEAST’ and which is on, daily, until Sunday 26 August, at half-past Midnight, in the Banqueting Hall at the Banshee Labyrinth (Venue 156). It’s a PBH Free Fringe production, so admission is free though donations are encouraged after the show. After the show, Liam agreed to talk a bit more about his work and what goes in to it.

CB: Hi Liam, please describe yourself, in three sentences or less?

LMcC: My name is Liam, I am a poet who writes about people you probably know. I am nice person who pretends to be mean because I am sad. Hashtag No Filter.

CB:Can I start by asking who you’ve been influenced by, as a writer and as a performer?

LMcC: Bill Hicks, Pussy Riot, Loki, Louie, Mog, Valerie Solanas, Victoria McNulty, Sam Small, Cee Smith, Nas, Kendrick Lamar, Alan Bisset, Sarah Kane. Leyla Josephine. There are probably a lot more, but those are the ones that come to mind right now.

CB: You played a lead role, as Billy Jnr, in Louie John Lowis’ ‘Inheritance’ – what did you learn from doing ‘straight’ acting and has that influenced the work you’ve done since, in any way?

LMcC: In terms of craft playing Billy taught me how to re-act. Until I played Billy, most of my work was solo performance, which doesn’t like space between lines. Billy taught me to milk a moment, and play off other performers.

But the biggest lessons I learnt were gained from working alongside Erin Friel. She is a brilliant conversationalist, when she listens you really feel heard (even if you are talking crap). Without meeting her, the difficult conversations I had to have to make BEAST would not have been possible.

Louie asked me to write some poetry for the play. He invited me to workshop it up at Platform theatre, and while I wrote it I got to watch him write. It was like getting invited to train with Bruce Lee. Seeing how fearless he was made me believe that any story I thought was worth telling could be told.

CB: You brought ‘BEAST’ to the Fringe for a 20 night run, going on-stage at half-past midnight every night in the Banshee Labryinth. This must have been a punishing experience, how did you manage to stay positive and keep your energy levels up, night after night?

LMcC: Stopped drinking, taking drugs and smoking weed. Suddenly I had a massive reserve of energy I could pull from. Good night’s sleep, lots of bananas water and coffees. At the end of the day, performing is a job and if you approach it with discipline and dedication, it’s really a pretty easy one. If you ever moan about it, you are in the wrong game.

As for staying positive: performing gives me a buzz. There is nothing better than it. It has a come down, but the come down just makes you want to go do it again. Which- lucky for me- there’s always another show. It’s when the run ends that I’m worried about!

CB: For a whole number of different reasons, ‘BEAST’ is a bit of a head-fuck. It is linear but not in the way that drama or spoken-word usually is. I’m fascinated by how you sit down and write and plan and develop chaos. What’s the process of putting a show together that’s very much a barrage of different moods and emotional states? Were you playing different sections off against each other, to get a particular effect? Or, in your mind, is there a clear emotional arc or progression going on?

LMcC: Everything I write begins with Star Wars Episodes 4, 5 and 6. Those films are the clearest; most efficient story ever written and any writer trying to create a narrative should study them.

This what I learnt from Star Wars. Take the world you live in, twist it a bit. Add a goody. Add a baddy. Give the goody a goal. Give the baddy a redemption. Give them both some pals. Get a few good solid laughs, a few solid cries. Break up the time you have into 3 chunks. Give each chunk it’s own unique flavour. First chunk is a microcosm of the whole thing. Put the darkest point at the end of the middle chunk. End on message for the kids at the last chunk. Tack on an epilogue that is a microcosm of the whole thing. To create chaos, just stick all that shit in a blender.

In my mind the story takes place over a weekend. Zara goes on a night out after work on Friday. Goes into work still steaming on Saturday night. Then she spends Sunday in her bed watching cartoons, before she drags herself out to go to mass. Finally she has a bath.

But it also takes place over an entire year during a break up cycle. First you want see your friends, meet new people and numb the pain with your poison of choice. Then your friends get sick of your chat. So you spend a few months manically working on whatever your passion is- or if you’re lucky enough to like your job you spend as much time at work as possible. Then the combination of the poison and pushing: you crash and burn. Then you finally spend some time on your own. Working it all out. At last: you emerge with all the lessons you learnt from that relationship.

CB: That leads me to ask about the way ‘BEAST’ keeps changing and evolving. The book is quite different from the first version of stage show, that you put on with Sonnet Youth back in March, and the Fringe show is different again. What’s driving this regular revision and re-working of the show? Are you finding different things you want to say, different ways of saying the same things or do you just think it needs to be re-configured for different audiences? Will there ever be a final, definitive version of ‘BEAST’?

LMcC: As a human being I am a work in progress. I react to everything said around this issue. And until the culture is done with the conversation: I don’t think I’ll be done chatting shit no.

As for a definitive version: I would like to film a 1-hour stand-up style special. Taking inspiration from Pussy Riot, I’d like to have a film playing above my head complementing the imagery of the poems with a subtitle track the reads the words I speak. Ideally the subtitles would be written in real time. I’d like to have a producer making live beats which sometimes become actual tunes, but mostly just complement my reading style. Add a dancer to my left and live musician to my right (playing a guitar, keyboard or horn).

If anybody wants in giz a shout xox

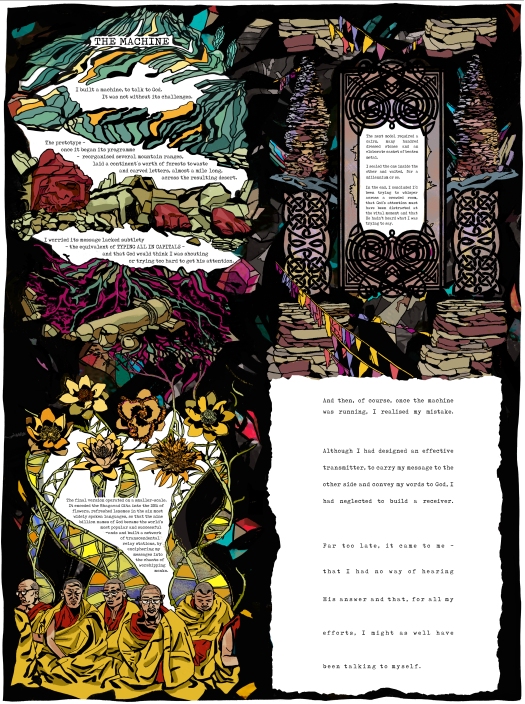

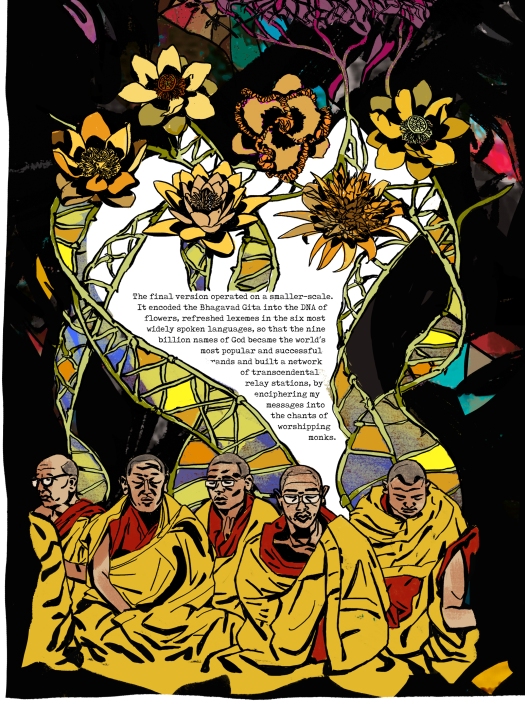

CB: Also, while we’re on the subject, a lot of the effect of the book version of ‘BEAST’ comes from the design and the lay-out of a lot of the poems – there are even poems presented a screenshots from Facebook or text messages on a phone. How much of the design of the book was your design, and how much of it was a collaboration with others – I see you’ve credited Bram E. Gieben, for example and Mark Penrose for the art.

And Ella Russell for the cover! Bram is a straight up pro. I told him what I wanted: he made a draft. Sent it to me. I said change this, change that. He did. Rinse-repeat till we’re both happy.

With Mark, I just took him round to my flat and read the poems I wanted pictures for. He latched on to certain images within the work and took it from there. He created 3 original pieces for the book, and the rest were ones that I was looking at while I was writing the book. So: he inspired me and I inspired him. We are both watchers, not very chatty and prefer to work in solitude. It was a bit like sending messages in bottles from each of our wee islands.

The Facebook poem was a gimmick, I consider it the weakest writing in the book. It was a daft story about an (the heaviest of air quotes here) ‘alpha’ male and a ‘beta’ male switching bodies freaky friday style that hopefully exposed both constructions of masculinity as sexist, selfish piggery.

The visual poems were me trying to be creative with having work published on a page. The context of art is important to me: even down to wether there is a bar near the stage. I didn’t want to be a spoken word artist writing a book- I wanted to write a book I’d like to read.

The book is my vision. But everybody needs some giants to stand on. I hope I can repay the favour to all my collaborators some day.

CB: Talking about collaboration more generally – both of the stage versions of ‘BEAST’ that I’ve seen relied, to a greater or lesser extent, on other people performing alongside you. The night I saw ‘BEAST’ at the Fringe, for example, Jade Taylor was playing the part of ‘Zara’ in the show. Does getting different people involved lead you to start seeing the material differently?

LMcC: Definitely. A good example of this is the poem Mirrors. I’ve heard it read by a variety of performers and each one brings a unique take on it. It is a poem that tries to put the listener in the shoes of the third person that exists in every relationship. The one that is neither partner A or partner B. The one that starts to come out as two people become a unit. They are a mix of all the insecurities and baggage both people carry around with them.

But when it is read out it becomes the readers. I like to read it imitating a very stoned person. Deep voiced, not caring and bored. This is not a good way to read a poem on stage. I saw Cee Smith read it with very intense anger at Mugstock. It becomes a frightening poem. One that really challenges the audience.

When Jade reads it, it becomes the private thoughts of woman trying to repress her emotions. It becomes a deeply sad piece. I feel the disappointment, the ‘just-get-through-this-and-tomorrow-it’ll-be-better-please. It becomes very hard to listen to. But; most of my work is hard to listen to. And it’s good that I am as challenged by it as the audience are.

CB: Do you look for collaborators that can surprise you, or people you can rely on to do what you expect them to do?

LMcC: I’m a pretty massive control freak. It’s hard to let go of any idea or piece. I like collaborators that can take direction well- even though I am not very good at giving it. It is rewarding when I am surprised by my collaborators, but I like to have a firm idea of what they will bring to the table. I don’t like being a follower. Maybe it’s arrogance, maybe it just comes with the vision. But a good leader knows when to take a step back. Like everything else, I am working on it.

CB: It seems to me that, in order for ‘BEAST’ to work, it has to be a shared experience between the people on-stage and the audience. It doesn’t strike me as a work that can just be watched or observed, the audience has to be willing to commit to what’s going on, men-tally and emotionally. How do you manage when the audience just isn’t willing to come with you, do you have any particular tricks, routines or strategies to get them onboard?

LMcC: The free fringe is probably the worst place on the planet to do this show. Every single poem requires some form of content warning, most punters expect comedians and there is a reliable group of english media types that go to free fringe shows to get drunk and heckle.

But I love a challenge.

Some audiences need their hands held through the material. A bit more inbetween chat, explaining the point I’m driving at. Other audiences don’t need any of that at all. When I judge it right, I feel completely in my element. But when I fuck it up- it can be a total car crash. But the point of doing 22 nights in a row is so I can learn every possible way of presenting the work.

The first thing I recommend is being vulnerable with the audience. If you can show them your heart then they will always pay you back for it. Never get angry. Be provocative, be passionate- but do not get angry.

And finally: shake everyone’s hand and ask everyone’s name. It’s an old commie thing my friend Jiggles told me about. In the show I twist it so that while I am shaking everyone’s hand a section of the S.C.U.M manifesto (by Valerie Solanas) describing the mental state of an alienated man is read out. This means my ‘getting to know you chat’ is undermined with the idea that all I am thinking about while delivering it is pussy and power. This sets the audience up for the dichotomy of Liam, nice wee guy who reads poems and the BEAST; a troubled, lonely aggressive sex pest. The two are eventually made one.

CB: Talking about shared experience, when we spoke after the show, you were telling me about some of the conversations you’ve been having with people who’ve seen ‘BEAST’. How important is it to you, that ‘BEAST’ generates discussion, that it creates a space and an opportunity for people who’ve been effected by the issues you deal with in the show, to share and talk about their experiences?

LMcC: It is very important to me. Obviously it takes an emotional toll, but I am asking the audience to go through a lot. You can’t ask people to go through an emotion without giving them a way out of it. Sometimes that means letting them tell you their story. Sometimes that means referring them to resources like Samaritans.

One night of the run I had a woman come in who was staying at the Shelter. After the initial shock of the material we sat down and had a long talk about art, healing and what we wanted in life. There were three people in the audience. One heckled the whole show, one left crying. But she stayed.

It was the best solo night of the run.

CB: However well intentioned you are, though, some people will hear about ‘BEAST’ and maybe come and see it and just think that you’re being exploitative and that you’re just out to shock people. How do you deal with the fact that there will be people who will never see past the surface? Does that matter, do you need everyone who sees it to ‘get it’ or have you made your peace with the fact that some folk just won’t.

LMcC: People will judge you no matter what you do. Might as well be yourself. I’ve never had thick skin. But a very wise man once said:

N’wit? Fuck ‘em.

-M.O.G

CB: And, talking about people not ‘getting it’, you’ve written a book and a show about a girl be-ing molested and abused in different ways, what do you say to the people who will inevita-bly think that, as a man, you shouldn’t be trying to tell this girl’s story, that the male gaze is never going to see things the way Zara would?

LMcC: I used to get shit off poets for not writing enough female characters. Now the beret brigade want to have a go at me because I did. Zara is me. At first I wanted to write about rape culture but I was not willing to talk directly about myself. I thought writing as a woman would make the work more palatable. But then Zara didn’t want to be me- and definitely didn’t want to be palatable.

I think the book never places you in Zara’s shoes. It is always observing her. The titles refer to her in the third person- to give the impression that she is being watched. Stalked. Either by the baddy or by the society she lives in. Zara is woman as seen through the eyes of a seriously disturbed man. In the same way that the man in Valerie Solanas’ S.C.U.M Manifesto is man through the eyes of a disturbed woman.

I ask female artists to perform Zara because it means the character becomes filtered through their experience. The exaggerations and untruths become either ironic, or obvious posturing. Each artist I have asked has had a different take on the poems, and brings their own baggage to the role. Which, in terms of audience experience, removes the worry that ‘oh a man wrote this so he can’t know what its reeealy like’. This is, regrettably, not present within the book.

At first I asked other poets to take on the role, but I came to the conclusion that it is ultimately disrespectful to ask an established writer to read your work in the guise of a poet. It means they may be credited with ideas they do not want to support, or do not come from their own soul. It may undermine their own work, and it leaves me partially obscured as the source. It means the audience never has to confront the fact that the words were written by a man.

CB: Which leads me to ask, there are easier ways to entertain people, you must have ideas for ‘easier’ shows that you could write, that wouldn’t seek to put you and the audience through the wringer in quite the way that ‘BEAST’ does. How necessary is it for you, that you’re do-ing this show, just now?

LMcC: Before I wrote this book I hadn’t spoken to my mum honestly since I was about 10. I wasn’t speaking to my brother. I’d go round to my dad’s maybe twice a year. I bullied everyone around me. I was living in a complete fantasy land and anyone who tried to challenge it would get undermined, belittled and and berated. This is especially true for my romantic partners.

Being better isn’t something that you achieve. It’s something you have to work on every single day. I fuck it up a lot. Having BEAST as an outlet for all the things I think and feel while I go through this process is incredibly valuable. It’s not a replacement for therapy, counselling or using helplines, but it has improved every single one of my relationships. With family, lovers, friends, drugs, money and work.

I could have just kept lying. I could have come up and done some banter and memes, made a few weed and poo jokes, hit them with some issues, tug some heart strings and walk away with some cash in my pocket. But I reject the clean-cut happy-chappy image. This book, this show, is me. I needed the audience to knows what kind of person I am and what kind of person I want to be . There is always going to be time for more weed bars.

CB: What would you do if, for some reason, you couldn’t do ‘BEAST’ – if you were told, you can write and perform something else but you can’t do that particular show anymore?

LMcC: I was told that. My best friends, my partner, other poets, my family all said it couldn’t be done. Some said it shouldn’t be done. I did it anyway. You can’t tell me nothing. What if you told Louie he couldn’t do Inheritance? What if you told McNulty she couldn’t do Confessionals? What if you told Loki he couldn’t do Poverty Safari?

I suspect they would say the same.

CB: And, finally , while we’re talking about doing other things, once your Fringe run has finished, what are you up to next?

LMcC: Taking the first week of September off to crash. Eating cake, drinking tea, playing zombies, Skyrim and FIFA. While I’ve been at the Fringe, I’ve been writing a pamphlet which will be called ‘Glasgow Uni Accent’, in which I will finally publish the old favourites (hash is great, shite craic etc), some new ones and a highlight reel of my in-between chat. Need a bit of a laugh after BEAST. The pamphlet will be complemented by a series of releases on BBC’s The Social.

I’m in the process of making an album from BEAST. I’d say I’m about 20% done so far. Still looking for collaborators and writing material for it. A rough and dirty version should be ready for the next GAG gig at the Govanhill baths.

I’d like to start a band. Been coming up with good names all my life- but I think next year is when I bite the bullet and just do it. I’m also working on a book of short stories set in Dingwall. But I think I need to go back there for a long time before it will be ready.

I’ve written a script for a TV show that I’m really excited about. But making a full 30 minute episode is a massive undertaking and I’d need some serious backing before I’m anywhere near bring it out. It’s great craic though.

But BEAST isn’t done yet. I want to see the world, and through the fringe I’ve made the connections that might make that possible. I’m sure you’ll be hearing from me and Jade again.

Liam McCormick is a Glasgow-based poet. He has had work featured on BBC 1xtra, BBC 2 and during the Scottish Cup Final 2017. His first collection ‘BEAST’ is available now from Burning Eye books.